Controlling neurons with radio waves…inhibition drives whisking behavior in mice…a new type of bright, fast, red fluorescent protein voltage indicator.

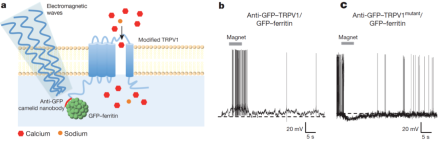

Radio waves regulate feeding behavior in mice by turning hypothalamus neurons on or off

Last year, BRAIN Initiative grantee Dr. Sarah Stanley, a neuroscientist at Rockefeller University, and colleagues developed a system for using radio waves to induce neural activity in mice. The researchers used radio waves or a magnetic field to directly manipulate ferretin (iron) nanoparticles tethered to temperature-sensitive TRPV1 ion channels, causing the channels to open and triggering action potentials in neurons in which the channels are expressed. Substituting a single amino acid within a sub-region of TRPV1 channel made the ion channel selective to negatively charged chloride ions, meaning that researchers can use radio waves to bring about neural inhibition, as well. In a new paper, published recently in Nature, Stanley and her team used the so-called “radiogenetics” system to activate glucose-sensing neurons in the mouse hypothalamus, which led to increased plasma glucose levels, lowered insulin levels, and ultimately stimulated feeding behaviors. Then, they used the radiogenetics system to inhibit the same class of neurons, which led to decreased plasma glucose, higher insulin, and suppressed feeding. If it proves to be robustly applicable in multiple systems, this method could offer significant advantages over both optogenetics—the technique for manipulating neural activity by shining light on genetically expressed light-sensitive ion channels—and DREADDs (designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs). The current report suggests radiogenetics does not require permanent implants and it can be used to potentially modulate activity in widely dispersed neuronal populations, unlike optogenetics. Further, the radio wave method could enable a more rapid response time than DREADDs.

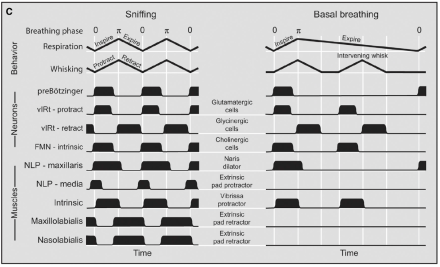

Inhibition, rather than excitation, drives rhythmic whisking in the mouse

Whisking—the rapid and repetitive back and forth sweeping of facial whiskers, or vibrissae—and sniffing are the primary exploratory behaviors of mice and rats. The rodent nervous system has to manage each of these behaviors so they do not occur at the same time. Figuring out how this occurs can help scientists understand more generally how nervous systems avoid antagonistic motor movements, i.e., movements that cannot occur simultaneously. NIH BRAIN grantee Dr. David Kleinfeld and colleagues observed that sniffing and whisking were driven by separate neural populations of the medulla called the pre-Botzinger complex (PreBotC) and the vibrissae-related region of the intermediate reticular formation (vIRt), respectively. They found that a rat’s breathing phase, which is closely related to its sniffing behavior, entrained the rhythm of whisking, consistent with unidirectional connections from PreBotC neurons that control vIRt neurons. In addition, Kleinfeld’s team found that vIRt neurons controlled whisking by rhythmically inhibiting the motor neurons that control facial vibrissae. The team also demonstrated that the synchrony in whisking between each side of the face relies on the respiratory rhythm, consistent with commissural connections between preBotC neurons in each hemisphere of the brain. The results of their study were published in a recent issue of Neuron.

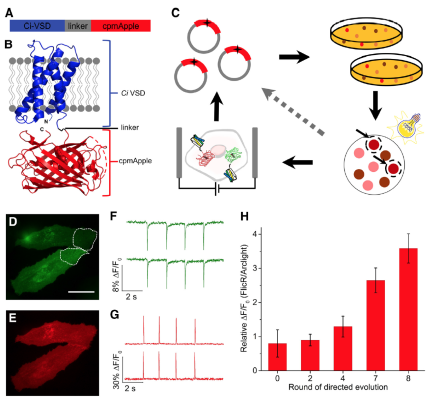

Researchers engineer first bright and fast red fluorescent protein voltage indicator

Fluorescent-protein-based voltage indicators enable imaging of the electrical activity of many genetically targeted neurons with high spatial and temporal resolution. Previous voltage indicators have been based on green fluorescent proteins (GFP). Attempts to derive a red fluorescent protein voltage indicator have resulted in weak and slow fluorescent signals. Now, researchers, led by NIH BRAIN grantee Dr. Vincent Pieribone of the John B. Pierce Laboratory, have engineered a red fluorescent protein voltage indicator, called FlicR1, that is comparable to voltage indicators based on GFPs in terms of signal strength and response kinetics. FlicR1 is the result of combining the red fluorescent protein cpmApple and the voltage-sensing domain from a phosphatase from the sea squirt Cionas intenstinalis. To optimize the response properties of FlicR1, which were recently reported in the Journal of Neuroscience, Pieribone and his team screened tens of thousands of variants that underwent random mutagenesis. The team demonstrated that the optimal variant of FlicR1 can be used to image single action potentials and voltage oscillations at 100 Hz in rats. FlicR1 has a few advantages over conventional GFPs, including lower phototoxicity and lower autofluorescence background. In addition, because FlicR1 is stimulated with yellow light, it can be used in conjunction with optogenetics-based proteins that are stimulated with blue light.